The village has been set ablaze, its once calm mountain vista transformed into a horizon of ash and flickering flames. The Big Bad looms over the cowering village leader. “Do you know why I’m here?” asks the Big Bad. The village leader rubs his singed gray facial hair. “No. Why are you here.” The Big Bad laughs. “Well then, I will tell you why I am here!” . . . Ladies and gentlemen, can’t we do better than this?

The Goal of Dialog

Dialog can run afoul for a wide variety of reasons. From an abundance of tropes to shallow conversations, many of these problems stem from a writer bending the characters around his or her will in order to adhere to the schedule of the script. Information needs to be conveyed; and characters and their motivations need to be introduced. However, first and foremost, dialog must serve the characters.

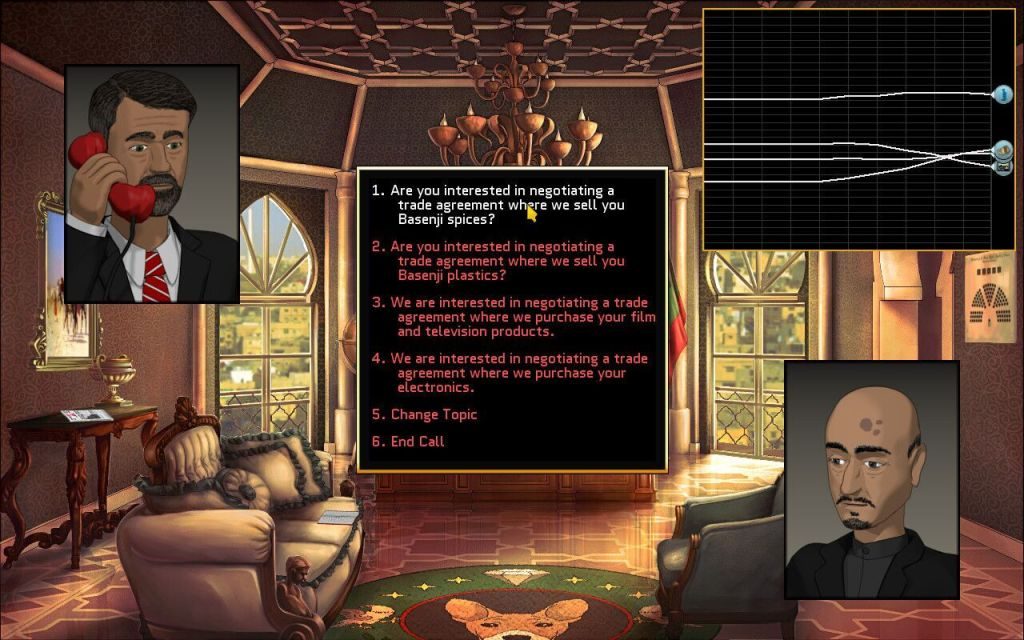

When characters want something, they talk. Whether it’s information on where the local bandit cave is or a need to express an emotion, when a character speaks, they are bartering with whoever is listening. They are seeking to get what they want while giving up the least in exchange. Likewise, the listener does not want to walk away empty-handed. While there exists some wiggle room for comedic dialog, good dialog is multi-layered. On one level, the characters are interacting in a contextually appropriate manner. On another level, they’re battling head to head to get what they want. Then on yet another level, they are advancing the plot, setting up characters, altogether doing all the behind the scenes stuff to keep the story from ending up a jumbled mess.

Direct vs. Indirect Dialog

At the heart of writing dialog is the concept of direct vs. indirect dialogue. Direct dialog is fairly simple:

“Do you know where the zombie dragon is?”

“Yes, it’s in the cave twenty miles to the north.”

One person asks a question, and the other responds directly. Direct dialog is very useful when using NPCs to convey setting, tone, or ambiance. It’s not something the player is supposed to think about: it’s all about conveying information efficiently. It’s also not very interesting.

If direct dialog is all about efficiency, then indirect dialog is all about luxury. This is where dialog can take on a life of its own and reveal things about the characters in a much more interesting way than being so direct about it. Let’s take the example from above and rewrite it as indirect dialog:

“Do you know where the zombie dragon is?”

“Fancy yourself a swing at ole’ Scalerot there, do ye? Well, I’ve sent scrawnier lookin’ lads than you to their deaths. Maybe if enough of ye come through the missus will get to feelin’ guilty and we can get off this dump and move into the city and I’ll finally have someone to talk to.”

Indirect dialog comes naturally to many who want to add color to their writing. When the characters are allowed to come alive, they shine and their individual personalities add flavor and depth to the setting. The listener could have just told the speaker where the zombie dragon lived, but he’s a lonely guy who lives with his wife in the middle of nowhere. He received payment in the form of someone listening to his ramblings.

By choosing to see dialog as a battle between wits or an intense barter, we open up our writing to the possibility of the characters acting in what’s best for themselves, rather than what’s best for the story. Setting and character both come alive, and with a good combination of direct and indirect dialog, the player can get through a game at a good pace completely immersed in the world you’ve created for them.

Dialogue for World Building

“Hello,” the man says. The woman looks at him and smiles, “The past ten years of our marriage has been a sham, I’m sleeping with the pool boy, and you’re not your daughter’s biological father. Also I’m hungry.” The man takes a moment and wonders if the woman could have been a bit smarter with her dialog.

Remember When?

In “Writing 101: How to Write Dialog That Doesn’t Suck,” I covered the basics of conversation between two or more characters, as well as the concepts of direct and indirect dialog. In my experience, I’ve run across countless writers who could wax poetic about a scene or a face in the mirror, but when it comes down to characters’ interaction within their world, I’ve only met a handful of (published) writers who could pull off good dialog. A good part of the skill to good dialog is in layered dialog: in creating double and even triple meanings in your characters’ words so that as the story progresses, the important stuff doesn’t become forgettable.

The Infodump

In our quest for well layered dialog it’d be good to start out with something that is categorically NOT layered dialog; and that is the concept of the infodump. Whether it’s expositional narrative or an evil monologue the infodump serves as a lazy method for describing the world and the current situation to the player. Often, this is information that the characters in the world already know but that the player must be brought up to speed on, but the infodump can also be seen in games where the character has amnesia or is a “beginner” of some sorts and must be explained the rules of the world.

While certainly there are things that the player needs to know, the infodump serves a singular purpose and is about as shallow and forgettable as a gray puddle. How much more interesting would it be to incorporate the lore of one’s game world into the characters’ and NPCs’ daily lives, into the music and set design, than to merely dump all the backstory onto the player in an opening cutscene?

The Thing, The Thing, and The Other Thing

So, simply put, layered dialog is dialog that has depth. It has more going on than just one thing. In other words, layered dialog is about the thing, the thing, and the other thing. So what are some examples? Let’s look at a villager NPC. The dialog for them could read something like, “Good morning! / Fine day today! / Great day for a walk!” We can layer this dialog by inserting some of the world into it, changing it to something like, “Praise be to you! / Albareth smiles upon us this morning! / Guess I’ll walk to the temple today.” We’ve changed a generic NPC into somewhat of a religious one now. His dialog not only informs the player about the NPC’s beliefs, but also clues the player into the temperament of the village and of the world the player is exploring.

We could take this dialog even further by introducing a second NPC, whose lines might look something like, “Mornin’. / Looks like everyone’s off praising that god instead of working. / My boy used to love days like these.” This particular NPC acts as a foil, or a counterpoint, to the temperament of the village. The dialog of the second NPC builds off of the religious temperament of the village and shows a counterpoint that reveals more story. The player is shown that, while most are religious, some choose not to worship, and for this particular NPC, there are hints that their loss of faith might be tied to the loss of their son. Throw in a tombstone in the village cemetery and you’re golden!

This Seems Like a Lot of Work . . .

No one said layered dialog would be easy! The one example I gave may be one case out of dozens found in a single village, town, or city, and this isn’t even taking main characters’ dialog into account. The goal of layered dialog is to inform the player tangentially, without attempting to communicate directly through them, instead letting the player explore the world and learn about it at their own pace. It’s hard work, but the reward is a fully fleshed out and believable world that the player can immerse themselves in for hours.

Dialogue for Voice Acting

Thanks MusicOomph.com for the photo.

Lots of writers love spinning yarns, weaving words, and waxing poetic. Many of us are guilty for being given a line and taking a paragraph (or two!) We’re at home when our writing shows up as words on the screen and we love complex, witty, dialog. However, when that dialog has to be performed, when a voice actor is tasked with taking our scribblings and using them to bring a character to life, we writers must take a slightly different approach.

Wait! Don’t Open That Door!

When I think of the perils of writing lines for voice actors in gaming, the first thing that comes to mind is the original Resident Evil. Granted, the voice acting itself is comically bad, but the writing isn’t really doing it any favors. The dialog itself is expositional at best (“Chris is our old partner, ya know”) and vapid at its worst (“Wow! What a mansion!”) Bad dialog writing becomes even worse when it is performed by voice actors. The key reason for these problems is, I think, a failure to approach dialog from the right direction. On one end, you have the characters and on the other you have the plot. Narration is often used to service the plot, while dialog supports the characters first and foremost. When dialog needs to exist to create exposition, it has already failed.

That’s not to say that dialog can’t be exposition, but in order for this to happen, it must first be about the character. Let’s look at the line from the Resident Evil video: “Chris is our old partner, ya know.” The line was used to convey two expositional qualities: first, that the characters have long-standing bonds with each other, and second, that these bonds are worthwhile. The best way to approach these kinds of situations is to talk around the exposition and focus on the character. If the character was a joker, they might say something like, “That unlucky bastard still owes me from our last card game.” A nervous character might say, “I’m worried about Chris. We shouldn’t be alone.” The best way to make dialog sound natural and pleasing to the ear is to focus on the characters. Be tangential to the exposition—talk around what needs to be said to drive the plot. When the written dialog is true to the characters, voice actors can better bring those characters to life through dialog.

Not Just Any Colloquialism

Colloquialisms are an important tool in dialog writing, but it’s important to keep in mind that different characters have different colloquialisms. In addition, a little goes a long way. The difference between a water fountain and a bubbler is the difference between a cardboard cutout and a character brought to life. On the other end of the spectrum, colloquialisms can be overused for comedic effect—see: stereotypical caricatures like Scooter from Borderlands (Catch a riiiiide!) And in the case of science fiction or fantasy settings, you might have to get creative and crank out a few unique colloquialisms specific to that world without beating the player over the head with it. The Shadowrun universe is great for this in specific- (Any bartender serving that drek deserves to get geeked.)

Embarrass Yourself

The final test to knowing if your dialog is ready to be performed is to perform it. Embarrass yourself by getting a couple people to read the dialog out loud. Does it sound weird at parts? What does the dialog say about the characters? Is there anything unbelievable? Does anything make you cringe? While things might sound fine in your own head or even when you read it out loud, getting someone else to perform the dialog will make any flaws glisten like crappy little turd gems.

In the end, there is only so much a writer to do before handing the reins over to the voice actors. There is definitely a level of trust when artists collaborate, so the least we as writers can do is not screw things up for the folks in the sound booths!

A shoutout and H/T to Dorian Karahalios for writing all of this content originally!

Please be sure to share this article if you enjoyed the read!

If you’re looking for a marketing partner to help make your game a success story, drop us a line at [email protected] and let’s chat!