Today’s guest post is by game designer and developer Will Nations and originally appeared on Will’s website.

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 can be found here.

Today’s the day! We’ve gotten an idea of what form Toki Sona-based narrative scripting will take, and we’ve examined some of the concerns regarding its integration and maintenance with code. Now we’re finally going to dive into my favorite part: theorizing the behavior of classes that would actually use Toki Sona and react.

The most brilliant illustrations of media, in my opinion, are those which exhibit the Grand Argument Story. These stories have an overarching narrative with a particular argument embedded within, advanced throughout the experience by the main character and those he or she meets as they personify competing, adjacent, or parallel ways of thinking.

But how are we to teach a computer the narrative and character relationships as they appear to us? Thankfully, a well-fleshed out narrative framework already exists to help us as we figure it out. Its name is Dramatica, and from it, we shall design the computer types responsible for managing a dynamic narrative: the Character, Agent, and StoryMind.

Brief Dramatica Overview

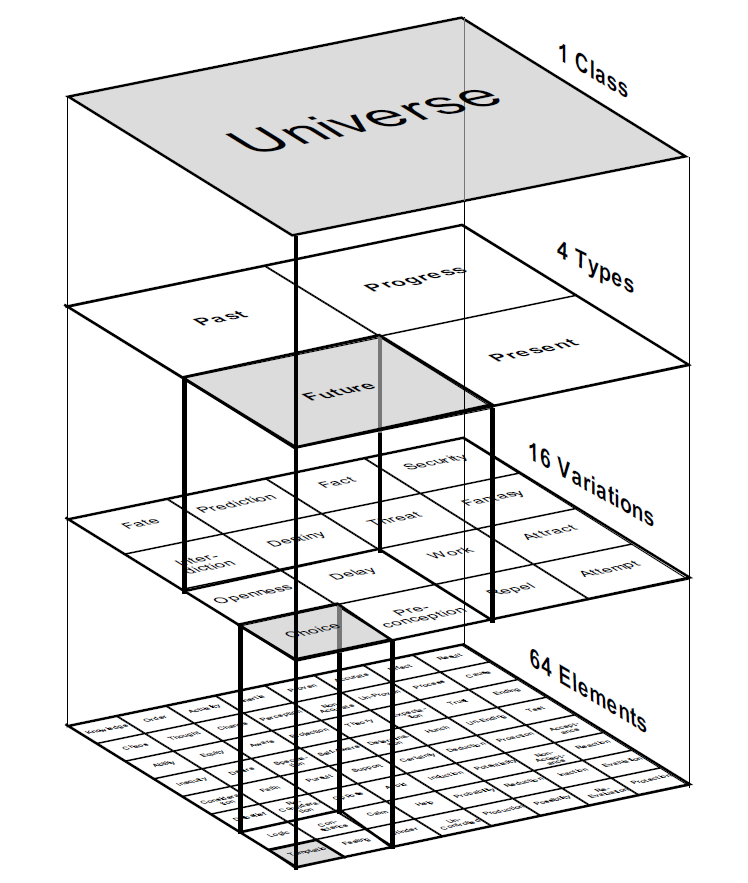

The Dramatica Theory of Story is a framework for identifying the functional components of a narrative. In its 350-page introductory book which is available for free on their website (the advanced book can be found over here too), it defines a set of story concepts that must exist within a Grand Argument Story in order for it to be fully fleshed out. If anything is missing, then the story will be lacking. To be honest, the level of detail it gets into is rather jaw-dropping as a writer. Its creators even had to create a software application just to help writers manage the information from the framework! How detailed is it? Check this out . . .

Dramatica defines four categories of Character, Plot, Theme, and Genre.

It also defines 4 “Throughlines” which are perspectives on the Themes.

- Overall Story (OS) = The story summarized as everyone experiences it. A dispassionate, objective view.

- Main Character Story (MC) = The story as the main character experiences it. The character we relate to, experiencing inside-out.

- Influence Character Story (IC) = The story as the influential character experiences it. The character we sympathize/empathize with, experiencing from the outside-in.

- Relationship Story (SS) = The story viewed as the interactions between the MC & IC. An extremely passionate, objective view.

Within Theme, there are four “Classes” that have several subdivisions within them.

- Universe: External/State => A Situation

- Physics: External/Activity => An Activity

- Psychology: Internal/Activity => A Manner of Thinking

- Mind: Internal/State => A State of Mind

One Throughline is matched to each of the Classes so that, for example, the MC is mainly concerned about dealing with a state of mind, the IC is trying to avoid a situation related to his/her past, the community at large is freaking out about the ongoing activity of preparing for and running a local tournament, and there is an ongoing difference in methodologies between the MC and IC that draws tension between them.

Each Class can be broken down into 64 elements. Highlighted: Universe.Future.Choice.Temptation Element.

For each Class, you select 1 Variation of a Concern per story. The four Plot Acts (traditionally exposition, rising action, falling action, and denouement) each then shift between the 4-Element quad within the chosen Variation. Since Variations each have a diagonal opposite, diagonal movements (a “slide”) don’t change the topic Variation as intensely as shifting Variations horizontally or vertically (a “bump”).

For example the Universe.Future.Choice variation has the two opposing Elements, “Temptation” and “Self-Control” plus the other two “Logic” and “Feeling”. Notice these are two distinct, albeit related spectra of the human experience that come into play when making decisions about the future regarding an external situation that must be dealt with. Shifting topics from Temptation to Self-Control wouldn’t be as big of a change as going to Logic or Feeling since the former deals with the same conflicting pair of Elements.

Each of those Elements can be organized with the Acts in a number of permutations. Three patterns arise, each of which have four orientations and can be run forward or backward (2). That gives twenty-four possible permutations for each Variation. Sixteen Variations per class, four Classes per story, and then times four again since each of the four Throughlines can be paired with a Class. Altogether, that comes out to 6,144 possible Plot-Theme permutations.

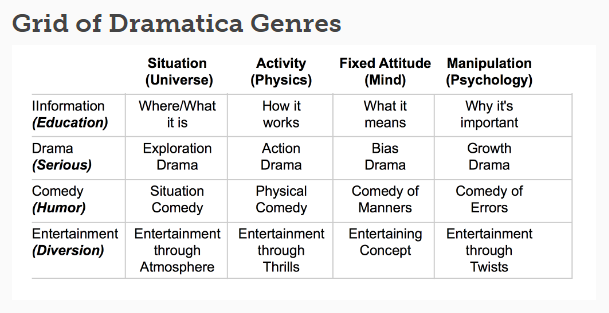

The Theme Classes are also matched up with Genre categories which can help the engine identify what sort of content to create at a given point of the story (doesn’t increase multiplicity).

The merging of Plot with Genre.

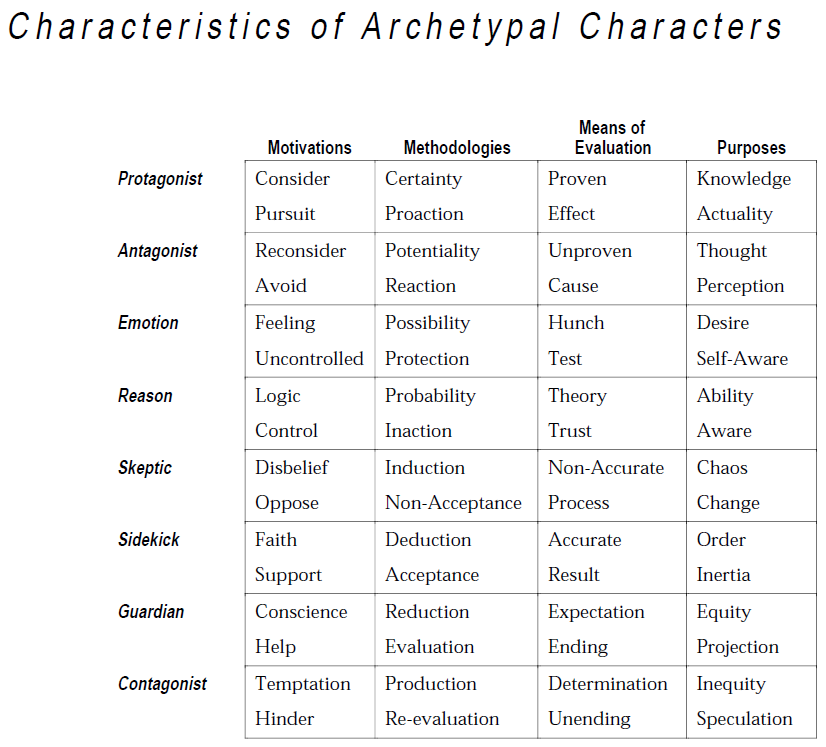

On top of that, there are the Characters to consider. There are eight general Archetypes, each of them composed by combining a Decision Characteristic and an Action Characteristic for each of four aspects of character: their reason for toiling, the way they do things, how they determine success, and what they are ultimately trying to do.

You can make any character by combining two Characteristics from two unopposed Archetypes. So, (7!) permutations of any given characteristic within an aspect (not matching up with an opposite for each of them).

5,040 * 4 aspects * 2 characteristics = 40,320 permutations of Characters, optimally.

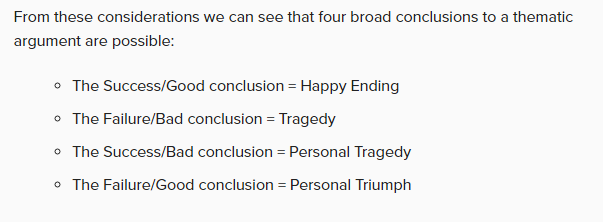

Finally, there’s the number of Themes that can be delivered by the external/internal successes and failures of the MC . . .

. . . and whether the MC and IC remained steadfast in their Class or changed (e.g. did they stay/change their state of mind?) and the success/failure thereof.

That makes 4 * 4 possible endings: 16.

PHEW! Okay, now, altogether that’s 16 endings * 40,320 characters * 6,144 plots…

Carry the 3 . . . there we go:

3.96 billion stories.

And that’s without even “skinning” them as pirate, sci-fi, fantasy. Take your pick.

Needless to say, these kinds of possibilities are exactly the sort of variation we should be looking for in procedural narrative generation. Even if you knocked out the Informational genre in the interest of counting only the non-edutainment games, that still leaves about 2.97 billion possibilities. Good odds, I say.

Also, keep in mind, any given video game will often times have several sub-stories within the overarching story, ones where minor characters have their own stories to explore and see themselves as the Main Character and Protagonist of their own conflict. In these stories, you, the original main character, may play the role of Influence Character (think Mass Effect 2 loyalty missions if you’ve ever played that: every character’s unique storyline is critically affected by the decisions you make while accompanying them for a personal, yet vital journey). Assuming any given story has, say, 9 essential characters (pretty small number by procedural generation standards, but pretty normal for children’s books), that would imply any single gameplay experience may involve 26.73 billion story arrangements.

It isn’t just Dramatica’s variability that makes it so appealing though. Each of these details are designed to be clearly identified and catalogued. This has two important consequences. The first is that the engine will know what goes into into making a good story and will therefore know how to create a good story structure from scratch. The second, and far more important to us, is that the engine will know when and how any of these qualities are not present or properly aligned. It will therefore understand what has happened to the story when the player changes things and how to fix them. Even better, because of its understanding of related story structures, it will even be able to adapt with completely new story forms should it wish to.

Head hurting yet? Fantastic! Let’s dig into characters as computer entities.

Characters & Agents

While Dramatica gives us the functional role of Characters, it doesn’t really flesh them out properly. Unfortunately, writers don’t really maintain a consolidated list of brainstorming material, but you can find several odds and ends around the Internet (list of character needs, list of unique qualities for realistic characters, and a character background sheet, for example). Any and all of these can be used to help flesh out and define the particular aspects of our Characters, beyond just their functional role.

The main interest we have with these brainstorming materials is to define a set of fields that an AI can connect Toki Sona inputs to. Given some Toki Sona instruction A, a definition of Character B, and a certain Context C, what course of action D should I take? Answering this question is the job of the Agent.

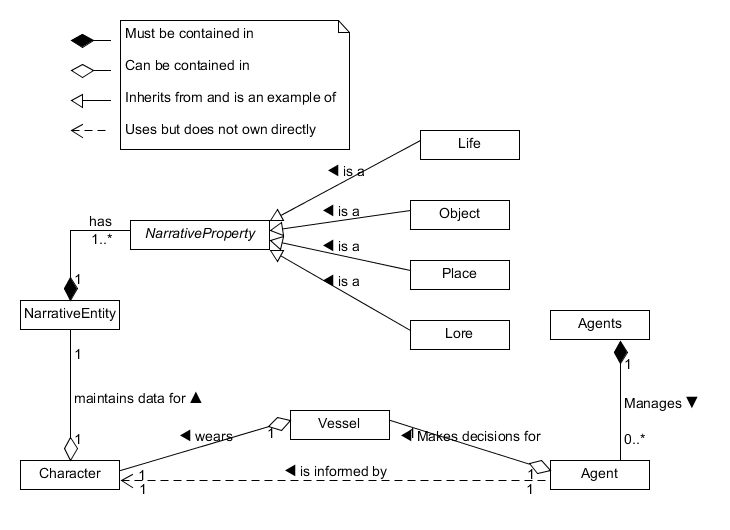

What exactly does an Agent entail? They would be the singular existence that represents the computer logic for the entirety of an assigned Character. In our case, we’re going to define a Character as ANY Narrative Entity that has (or could resume having) a will of its own. A Narrative Entity would simply be anything that requires a history of interactions with it to be recorded such as a Life, an Object, a Place, or a piece of Lore.

Notice that characters don’t have to be living beings specifically. For example, an enchanted swamp may have an intelligence living amongst the trees. It would most certainly be a Character; however, it would also definitely be a Place that people can enter, exit, and reside in. As a swamp entity would be the embodiment of both the land, the plants, and the animals within, one could also extend its attributes to Life as well. As a result, we’d have the swamp Agent that accesses the Character which in turn maintains properties of both the Life and Place for the swamp Narrative Entity.

Sample low-effort UML Class Diagram for the Agent Subsystem (made with UMLet).

In the diagram above, we specify that a single Agent is responsible for something called a Vessel rather than for a Character directly. What’s more, the Vessel can “wear” several Characters! What is the meaning of this?

Let’s say we wished to create a Jekyll & Hyde story. Although Jekyll and Hyde have different personalities, they also share a body. Whatever one is doing, wherever one is, the other will also be doing the moment they switch identities. This relates back to assets too. Whatever one sprite/model animation will be doing, the other will also be doing when those assets are switched to another set. In this way, Characters and Vessels are fully changeable without affecting the other. A multiple personality character might change Characters while not changing Vessels. A shapeshifting character might change Vessels while not changing Characters. In the case of Jekyll and Hyde, it would be a swap for both Character and Vessel as their personalities and bodies are BOTH different, but it will always be tied to the same location and activity at the time of switching.

So, the Agent is just an AI that doesn’t care what it’s controlling or to what ends. It looks to the Character to figure out what it narratively should and can do, and it issues instructions based on that to the Vessel. It doesn’t care whether the Vessel knows how to do it. It simply assumes the Vessel will know what the instructions mean. In the process, we’ve divorced the concept of a Character 1) from the in-story and in-engine thing that they are embodied as and 2) from the logic that figures out what a given Character should do given a set of Toki Sona inputs from the interpreter.

The last important thing to note about the Characters and Agents here is that the Agents are informed, context-wise, by their associated Characters. As such, an Agent’s decisions are constrained by their Vessel’s current Character; only its acquired knowledge, background of experience and skills, and personality will invoke behavior. An Agent will therefore factor into its decision-making the Character’s history of perceptions, likes and dislikes, attitude, goals, and everything else that constitutes the Character. It then translates incoming Toki Sona instructions into gameplay behavior. For example, what might a Character do if asked, “What do you know about the aliens?”

Maybe they don’t know much about the aliens. Or maybe they do, but it’s in their best interest to only reveal X information and not Y. But maybe they also really suck at lying, so you can see through it anyway. How will they know exactly what to say? How will they say it? Does the personality invite a curt, direct response, or do they swathe the invading aliens with adoration and delight in a giddy, I’m-too-obsessed-with-science kinda way?

The StoryMind

Finally, we address the overall story controls: the StoryMind. In Dramatica, the StoryMind is the fully formed mental argument and thought-process that the story communicates. In our context, the StoryMind is the computer type responsible for delivering the Dramatica framework’s StoryMind. It understands the possible story structures and makes decisions regarding whether the story can reasonably deliver the same themes with the existing Characters and Plot or whether it will need to adjust.

The StoryMind will have full and total control over that which has yet to be exposed to a human player within the story. It’s job is to generate and edit content to deliver a Grand Argument Story of some kind to the player. What might this look like?

Story time:

Typical Fantasy RPG world/game. You’re a strength-and-dexterity-focused mercenary and you’ve developed a bit of a reputation for taking on groups of enemies solo and winning with vicious direct onslaughts. You’re walking through town and come across a flyer about a duke’s kidnapped heir (one of a few pre-generated premises made by the StoryMind). You ask a barkeep about it (and it alone), so the StoryMind begins to suspect that you may be interested in pursuing this storyline further (rather than whatever other premises it had prepared for you). It therefore begins to develop more content for this premise, inferring that it will need that story information soon. In fact, it takes the initiative.

You are blocked in the road by a woman named Steph who overheard you outside the bar and wishes to accompany you on your journey to rescue the heir. She says that she’s a sorceress with some dodgy business concerning the duke and she needs a bargaining chip. Let’s say you respond with, “Sure. I only want the duke’s money,” (in Toki Sona of course). All of a sudden, the StoryMind knows a couple of things:

- You care more about the reward money than pleasing the duke.

- Because you have already invited risk into your relationship with the yet-to-be-met, quest-giving duke, you are even more likely to behave negatively toward this particular duke and his associates in the future. You also might have a natural bias against those of a higher social status (something it will test later perhaps).

- You have some level of trust towards Steph, though it’s not defined.

- You are not a definitive loner. You accepted a partnership, despite your past as a solo mercenary. But how deep does this willingness extend? It’s possible it might be worth testing this too.

Since you may have related goals, the StoryMind sets her up as the Influence Character. It randomly decides to attempt a “friendly rivals / romance?” relationship (partnership of convenience), modifying her Character properties behind the scenes so that she is similar to you (based on your actions and speech).

Along the way, a group of goblins ambush and surround you both, so you dash in to slaughter the beasts. The StoryMind may have been designing Steph to support you, but unbeknownst to you, in the interest of generating conflict, it changes some of Steph’s settings! Steph yells for you to stop, but you ignore her and slash through one of them to make an opening. In response, Steph sparks a blinding light, grabs your hand, and runs away in the ensuing chaos.

As soon as you’re clear, she starts yelling at you, asking why you wouldn’t wait. After you get her to calm down a bit and explain things, she confides that she is hemophobic and can’t stand to see, smell, or be anywhere near blood. She’d prefer to stealthily knock out, sneak past, trick, or bloodlessly maim those who stand in her way. How will you react? Astonishment? Scorn? Sympathy? Is this a deal breaker for your temporary partnership? Remember, she’s always paying attention to you, and so is the StoryMind. This difference in desired methodologies is but a small part of the narrative the StoryMind is crafting.

- Throughline Type: Class.Concern.Variation.Element, Act I

- Description

- Genre

- Overall Story Throughline: Physics.Obtaining.SelfInterest.Pursuit

- A dukedom heir has been kidnapped.

- Entertainment Through Thrills: Pursuit of an endangered royalty.

- Influence Character Throughline: Mind.Preconcious.Worry.Result

- Steph is worried about how to deal with her hemophobia. (StoryMind shortly generates this afterward=) She can’t find work beast-slaying or healing because of it, and is now low on money. The duke is evicting her, despite her frequent requests for bloodless work as payment. Everything’s so stressful, and it’s all because of that stupid blood!

- Comedy of Manners: the almighty sorceress, the bane of beasts and harbinger of health, brought down by the mere sight of blood.

- Relationship Throughline:

Psychology.Conceiving.Expediency.Protection- You’d prefer to hack away at enemies, but she can’t stand blood and prefers alternative approaches to removing obstacles. As such, you each have different manners of thinking about how you feel obstacles should be dealt with.

- Growth Drama

- Main Character Throughline: Universe.?

- If nothing interrupts the progress of the other 3, the StoryMind is fit to throw external state-related problems your way, and these problems will necessarily dig into deeper, thematic issues. For example…

- Universe.Progress.Threat.Hunch

- You eventually learn that those who took the heir have loose ties to the duke himself. Since you’re in pursuit to rescue him/her, you have a hunch that you may be a target soon as well. You need to unearth the mystery surrounding this. Does this impact your ability to trust the various characters you come across?

- Entertainment Through Atmosphere: You’re experiencing a fantasy world!

And to think, if you’d just said, “No, thanks. I’m more of a loner,” at the beginning, Steph might instead have developed as a hindering rival Influence Character who tries to steal the heir for herself, popping in and out of the story when you least expect it! Does she even know about the duke’s possible relation to the kidnapping? Too bad we’ll never find out. After all, you didn’t say that. The characters and experiences in this world are real and permanent. You live with your choices, build relationships, and engage with a game world that truly listens to you, more intimately than any other game has before.

Conclusion

I have found that Dramatica is an excellent starting point from which to build story structures and inform our StoryMind narrative AI of how to craft and manipulate storylines and characters. I hope you too are interested in the potential of this sort of system so that one day we might see it in action.

Also, it’s entirely possible I might have slightly messed up some calculations concerning the Dramatica system as the book doesn’t do a great job of clearly defining the relationships in one place (it’s sort of scattered about in the chapters). As far as I can tell, I’ve got them right, but I don’t terribly favor my math skills. I’d be happy to correct any mistakes someone notices.

In the future, expect to find an article diving into the hypothetical technical representation of Agents: their relationships, perceptions, and decision-making. Again, I’d love to hear from you below with comments, criticisms, and/or questions. Cheers!

Will Nations is a game designer and developer dedicated to evolving the way stories are told. He is an active member of the Christian Game Developers Facebook group and /r/gamedev Reddit pages. His free time is spent developing tools to assist the game development industry overall.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this blog post and want to receive advice, analysis, and tutorials from industry veterans and marketing experts, we have a free mailing list that offers just that! You’ll receive weekly blog post roundups, in-depth tutorials and guides, and stories from experienced industry professionals. Plus, when you sign up you’ll receive a free copy of our eBook, “The Definitive Guide to Game Development Success”. Thanks again, and hope to see you on our mailing list!

> Sign up here! <