Today’s guest post is by Ryan Hewer. He is the founder of Little Red Dog Games, creator of the geopolitical strategy Rogue State and the upcoming rogue-like space adventure survival game Deep Sixed.

1. You’re Building a Mirror, Not a Picture Frame

Our original vision was to build a game about the kind of countries that, for obvious reasons, wouldn’t typically get a game made about them. I thought it’d be kind of interesting to make a game about Qatar or Oman—countries that have a story to tell that goes a little deeper than, “This is where there is lots of violence.” I wanted to create a Middle Eastern country that borrowed elements from a lot of different places and had a lore of its own that seemed familiar without feeling like it was shining a light on a country that would make the daily news in the United States. And as people played it, the comments came back: “This is a game about Syria/Iraq/ISIS,” and, “This game should focus more on Russia trying to keep you in power.” And my favorite: “This is a game about a country you would read about on CNN.” When making a geopolitical strategy game, players will make it into what they want it to be. If you try to avoid a political agenda, players will fill in the blanks themselves so they get the story they want to play. Let them.

2. Mixing Genres Isn’t Always a Good Thing

I wanted to create a strategy game that felt like an adventure game. In doing so, we used an engine that wasn’t ideal for the task and simultaneously created a game that managed to alienate strategy gamers that weren’t interested in moving a character around and looking at things as well as adventure gamers who didn’t care for all the strategic maps, charts, stats, and progression. We have learned from this and will be abandoning the adventure game roots in Rogue State 2 . . . Oops, did I just say Rogue State 2?

3. Finding Authentic Middle Eastern Accents from English-speaking Voice Actors is Really, Really Hard.

I wish we gave ourselves more time for this. I’ve got an ear for accents and a lot of regional experience in the Middle East and North Africa. Despite the many channels we pursued over several months, finding authentic male and female voice talent from the region on our limited budget that we could rely on for the large body of audio required was almost impossible. We had to make some sacrifices along the way and turn to trusted professionals who put in the hours to give their best approximations. I’m extremely grateful to all our actors who helped us out—but every time I read a criticism of the authenticity of the accents I cringe as if I’ve been stabbed in the gut. Thankfully, we’ve come a long way since then and have built up relationships with a lot of theatre schools in the region. Take-home message: Go visit a theatre school and meet people. Bring money.

4. Everything Old is New Again

A lot of the little decision points and lighthearted moments that litter the game are derived from two years’ worth of current events during the development period. I worried that by the time we launched, those wink-and-nudge moments would long become tired-out memes that you’re only still seeing on the Twitter feeds of fast-food chains. (“One does not simply order a Wendy’s Baconator.”) Turns out that wasn’t a problem at all, and sometimes the news just happens to align with what you’ve already got.

5. Localize

We found surprise success in South America and Eastern Europe and heard many times over that they wished the game was available in their native languages. Don’t overlook the power of localization—particularly indie developers looking to build a more global fanbase.

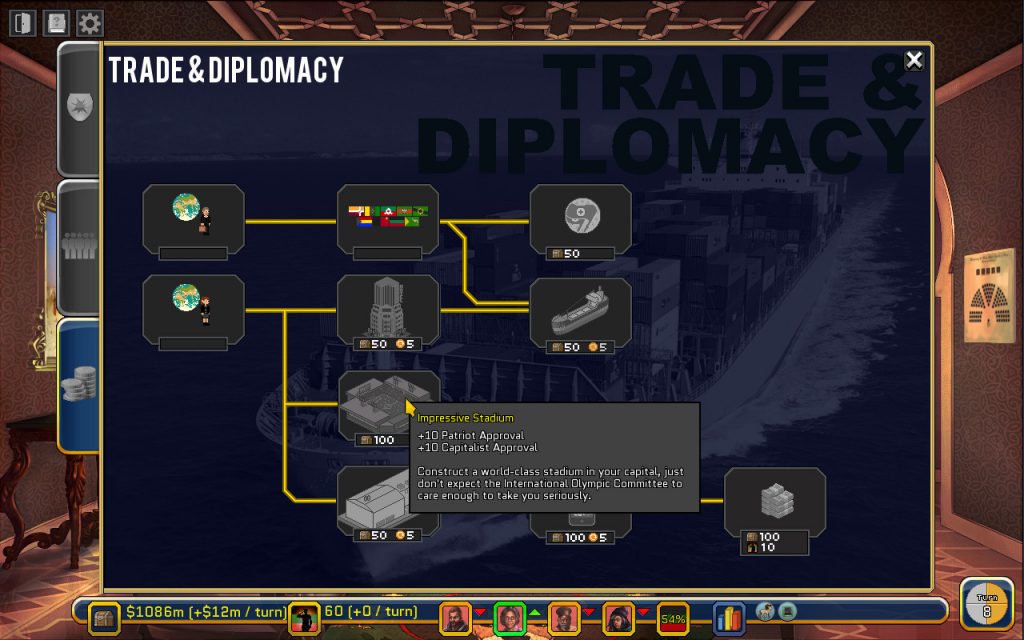

6. Nuanced Politics are Very Appealing to Gamers.

From the very start, we wanted the game to be more complicated than states of war and peace. We wanted players to manage political relationships that included strong development coalitions, Cold-War-invoking arms buildups, important trade relations with antagonizing countries, and diplomacy that was built upon finding common ground. I want to think our players really appreciated this; people who just opened up with invading their neighbors would find themselves caught in a protracted war that provided little returns for the aggressor.

7. Accept Criticism

People will expect unreasonable things for the price of a nice sandwich. People will buy your game on sale for two dollars and compare it to a game that regularly retails for thirty. It’s not fair, but it’ll happen and you’ve gotta smile and not take the bait. Listen to your fans and to the most constructive suggestions, and bow graciously to your critics (keeping your eye-rolls behind the monitor).

8. If You Build It, They Will Break It

You may go into this with a very specific vision that doesn’t align with your players. So why not invest in modding tools so people can make the game into what they want instead? I wish I appreciated the power of this when we published. We’ve learned a lot since then.

Sign up for Little Red Dog Games’s mailing list for Deep Sixed and be the first to receive news, updates, and exclusive content!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this blog post and want to receive advice, analysis, and tutorials from industry veterans and marketing experts, we have a free mailing list that offers just that! You’ll receive weekly blog post roundups, in-depth tutorials and guides, and stories from experienced industry professionals. Plus, when you sign up you’ll receive a free copy of our eBook, “The Definitive Guide to Game Development Success”. Thanks again, and hope to see you on our mailing list!

> Sign up here! <